01/ 04

Join the millions who’ve passed the first time.

Instructor Ranking

4.8/5

Pass Perfect’s live class instructor ranking in 2024.

CSAT Support Rep Ranking

4.6/5

Pass Perfect’s customer satisfaction ranking in 2024

Popular Courses

SIE + Series 7

Prices starting at

$

229

00

SIE

Prices starting at

$

99

00

Series 7

Prices starting at

$

199

00

Series 65

Prices starting at

$

199

00

Series 63

Prices starting at

$

99

00

Series 66

Prices starting at

$

155

00

Series 24

Prices starting at

$

375

00

Preparing Passers for Over 40 Years

A proven past, exciting present, and promising future — all driven by a team of people proud to help others reach their career goals.

Pass Perfect Features

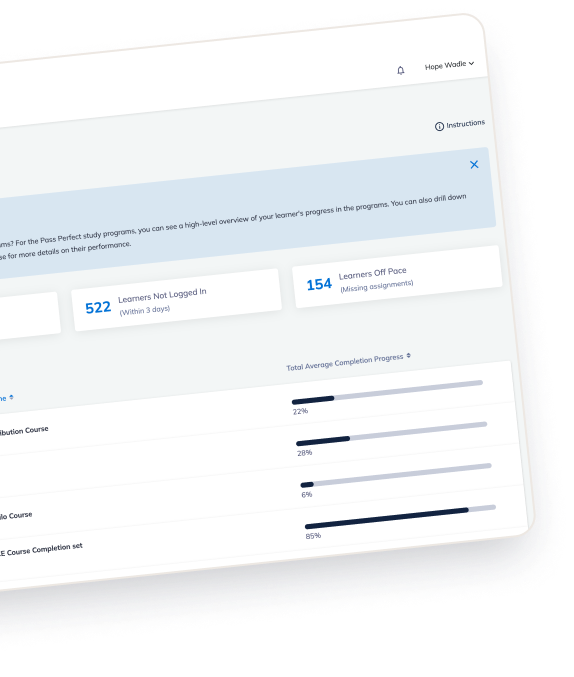

State-of-the-art Learning Management System

No other securities exam preparation is backed by the experience and resources of Pass Perfect. With the most up-to-date content, delivered in ways that best work for you, you will join the millions we’ve helped get licensed.

50k+

Passers this year

Proficiency Dashboard

A user-friendly dashboard that provides high level performance data that puts you in control so you know exactly where you are, what’s coming next, and where you need to focus.

Question Database

With 3x more questions than competitors, Pass Perfect is the only online interactive securities prep to help you learn it all.

Chapter, Mastery, and Final Comprehensive Exams

Knowledge tests at the end of each milestone, and (unlike many competitors) you can take them an unlimited number of times.

Calendar Customizations

The study plan makes for a smooth learning experience from start to finish. Providing a daily schedule of study recommendations, it organizes tasks across the calendar.

Check Your Understanding

Practice questions after each section to show whether you grasp the material or not, and recommend next steps.

Comprehensive Study Guide

Comprehensive online and eBook study guides for you to help organize your learning goals.

Study Smarter, Pass Faster

Launched in early 2024, these latest enhancements to the Pass Perfect learning management system bring even more value to our learners.

Reimagined Content

We’ve optimized our courses to reduce study time and boost pass rates for faster licensing. In Series 66, we’ve cut the fluff for 36% faster overall study time, and cut reading time by 25% in Series 7!

Proficiency Dashboard

See at a glance where you’re doing well, or where you need a little extra work. The new dashboard puts you in control so you know where you are and where you need to focus.

Partnerships

Corporations

We’ve pushed the boundaries of traditional learning with an innovative learning experience designed to support learning and development leaders and corporate administrators in their goals to help your employees gain the highest quality financial education anywhere.

Partnerships

Universities

Our SIE programs not only adapt to each learner’s individual needs, but can also be customized for your university’s overall needs. Whether you want to launch an entirely new program or just simplify a current one, we’re here to help create your perfect solution.

What everyone is saying...

Year after year, Pass Perfect receives high customer satisfaction ratings. We value the confidence our clients have in us and we will never stop working towards tomorrow’s solutions — because our future is all about helping you prepare for yours.

I HIGHLY recommend Pass Perfect! I didn’t come from a finance background and passed the SIE, Series 6, and 63 first try using Pass Perfect. One of things I love about it compared to other learning programs is the various resources it provides. The program caters to different learning styles and I wouldn’t have been as successful without all the many practice tests it provides. Utilize all the resources and you will pass for sure!

Rebecca

February 2024

Very happy with my pass perfect experience. I thought the test prep prepared me for the exam, in fact maybe slightly more difficult. Peter was particularly helpful, as he was available for one-on-one tutoring, focusing on areas I felt I needed to strengthen. Happy to be done and very appreciative for the guidance through the process!

Ryan Baker

March 2024

Pass Perfect is well….. Perfect! Very informative and to the point. It is great preparation for the career road ahead.

Noah Polvado

April 2024

Easy to follow to material. The system tracks your proficiency so that help you to know what items you need to work on more. Instructor very patient and answered all questions. Was thoroughly with all the material.

Stephanie Mays

March 2024

I cannot recommend Pass Perfect / their Training program enough. I studied for the S-10 and failed my first attempt while using STC! I switched to Pass Perfect for my 2nd attempt and I PASSED - All because of the way this program is built out. The videos, the classes, the QUICK BOOKS, all of it! This program challenges you more than any other program in the game. The tutor’s are also super helpful and really cross your t’s and dot your i’s. 10/10 recommend this program for your Series 10!

Kara McDade

May 2024

Pass Perfect has been the ideal partner for our firm. The study materials for different FINRA licenses have been expansive and helped our reps complete their requirements and pass their exams.

Anonymous

B2B Customer