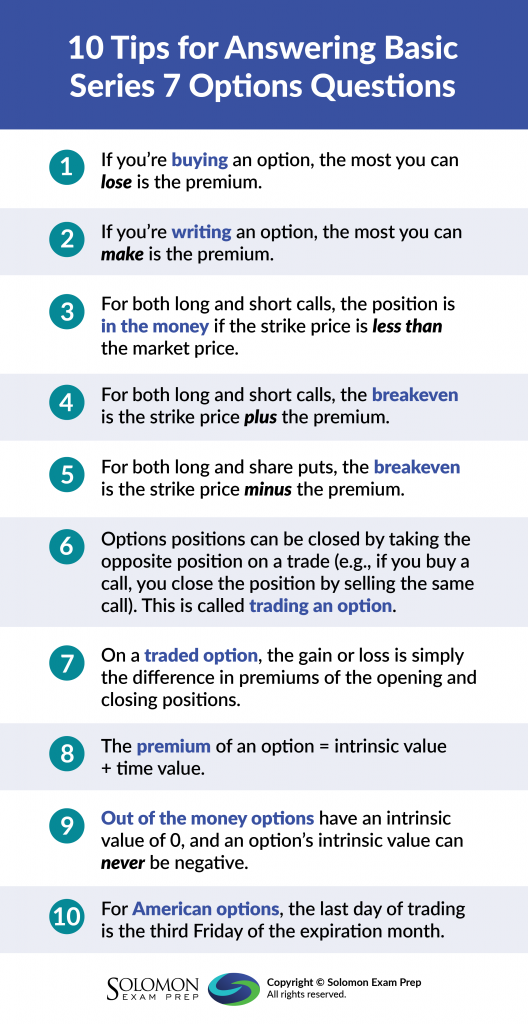

Options are a topic that many taking the Series 6, Series 7, Series 65, Series 66, and SIE exams have to deal with. One of the biggest problems that students have with options questions occurs when they are asked to calculate gains and losses on exercised options. As long as you understand a few basic points, these types of questions can be a breeze and definitely nothing to lose sleep over.

First of all, let’s remind ourselves of what an option is. An option is a contract between two parties that gives the buyer of the contract the right to buy or sell an underlying asset to the other party in the future for a specific price. The specific price is called the “exercise” or “strike” price. The seller of the option, on the other hand, is obligated to buy or sell, at the strike price. The option to buy is a “call” option, the option to sell is a “put” option.

To calculate gains and losses on exercised options, you first need to understand what is happening as a result of an options transaction. When an option is exercised, that means its holder chooses to either buy or sell the underlying security at the strike price. With an exercised call option, the holder purchases shares of the underlying security from the options seller; with an exercised put option, the holder sells shares of the underlying security to the options seller. The sale in each case occurs at the option’s strike price.

Buying – Exercised Call Option

When a call options holder exercises her option by purchasing the underlying shares, she must add the cost of those shares to the premium she paid to obtain the option in the first place. This sum represents the option holder’s total money spent as a result of her options transaction. If the option holder then elects to sell the underlying securities she’s just purchased at their current market price, the money she receives from the sale will be money she takes in. To calculate her gain or loss, subtract the money she paid out from the money she took in. It’s as simple as that.

So, if, for instance, Marie paid $200 in premiums to purchase a call option with a strike price of $20 and then exercised the option by purchasing 100 shares of the underlying stock, the money she spent as a result of her options transaction will be $2,200 ($200 premium paid + $2,000 purchase price for underlying securities). If she then sells those 100 shares at the market price of $25, she will receive $2,500 in sales proceeds. Subtracting the money she spent from the amount she received will result in a $300 gain ($2,500 sale proceeds – $2,000 purchase price – $200 premium paid = $300 gain.)

Buying – Exercised Put Option

In order for a put options holder to exercise his option, he must have 100 shares of the underlying security to sell to the options seller. That means he needs to go out in the market and purchase shares at their market price. The money he pays for those securities plus the premium he paid to purchase his put option in the first place represents money spent as a result of his options transaction. The options holder will then sell those 100 shares to the options seller at the strike price. When he does this, he receives the sale proceeds. Subtracting the money spent on the put from the sale proceeds will result in the put investor’s gain or loss.

So, if, for instance, Pierre paid $300 in premiums to purchase a put option with a strike price of $30 and then purchases 100 shares of the underlying stock when its market price drops to $25, he will have spent $2,800 as a result of his options transaction ($300 premium + $2,500 purchase price for underlying shares). He will then sell those 100 shares to the options seller at their strike price of $30 and take in $3,000 from his sale. Thus, Pierre will make a total of $200 on his options transaction ($3,000 sale proceeds - $300 premium – $2,500 purchase price = $200 gain).

Selling an Option

Now let’s look at gains or losses from the perspective of an options seller. Remember that when someone sells an option, he receives the premium from the options buyer. If the option expires unexercised, the seller gets to keep his entire premium received, which represents his maximum potential gain. If the option is exercised, he will either be required to sell shares of the underlying security to the option holder in the case of a call option or buy shares from the option holder in the case of a put option. Each of an exercised call or an exercised put option transaction is made at the option’s strike price.

Selling – Exercised Call Option

When a call option is exercised, the option seller must obtain 100 shares of the underlying stock to sell to the options holder. To do so, he will have to purchase the shares at their current market price, which will be higher than the option’s strike price. He will then sell them to the option holder at the strike price. The money he takes in from the sale is added to the premiums he received when shorting the option, and this totals the money he takes in as part of his options transaction. The money he paid to obtain the underlying securities is the money he pays out. Subtracting the money he pays out from the money he takes in results in his overall gain or loss.

For example, let’s say Michael sells a call option with a strike price of $50 and receives premiums totaling $500. If the option is exercised, and Mike purchases the underlying shares at $55, he will have paid out $5,500 as a result of his options transaction. At the same time, he will have received $5,500 ($500 premium + $5,000 strike price). Thus, Mike will break even on this transaction; money taken in will be equal to money paid out.

Buying – Exercised Put Option

When a put option is exercised, the option seller must purchase 100 shares of the underlying security from the options holder at the strike price. This represents money the options seller pays out. The options holder has already received the premium when she sold the option, and after purchasing the 100 shares, she can sell them for their current market price. The combination of the seller’s sale proceeds and the premium received represents money taken in. Subtracting money paid out from money taken in will result in the investor’s gain or loss.

Let’s say Maribel shorts a put option and receives premiums totaling $400. The option has a strike price of $40, and the option holder exercises it when the underlying stock is trading at $35. This means Maribel is obligated to pay $4,000 total for the 100 underlying shares. This is money she pays out. She has already taken in $400, and if she chooses to sell the underlying stock at its current market price, she will take in an additional $3,500 in sales proceeds. This means she will receive a total of $3,900 from his options transaction ($3,500 sale proceeds + $400 premium) and paid out a total of $4,000. As a result, she has lost $100 on his options transaction ($3,900 money in – $4,000 money out = -$100).

As long as you understand what is occurring when an option is exercised, calculating gains and losses is as simple as comparing the money the investor takes in to the money she pays out. Calculating gains and losses on exercised options requires an understanding of the transaction and some simple math. Follow the guidance above and you will be able to correctly answer this type of question on your securities licensing exam.

For more helpful securities exam-related content, study tips, and industry updates, join the Solomon email list. Just click the button below: